|

Tadayoshi Kohno (Yoshi Kohno) (he/him)Professor Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington UW CSE Security and Privacy Research Lab UW Tech Policy Lab Medium Blog Email: yoshi@cs.washington.edu |

At UW. Professor in the Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering. Adjunct Professor in Electrical & Computer Engineering, the School of Information, and the School of Law. Associate Director for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access in the Allen School. Co-director of the Security & Privacy Research Lab. Co-director of the Tech Policy Lab.Prior to UW. BS, University of Colorado (with Hal Gabow and Evi Nemeth). PhD, UC San Diego (with Mihir Bellare).

Committees. USENIX Security Steering Committee (2012-Present). Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Advisory Board (2020-Present). Partnership on AI (PAI) AI Safety Steering Committee (2022-Present). The International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences (2022-Present). Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS) Steering Group (2011-2014). National Academies Cyber Resilience Forum Member (2014-2018).

Awards. Technology Review TR-35 Award (2007). Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship (2008). NSF CAREER Award (2009). IEEE S&P Test of Time Award (2019 and 2020). ACSAC Test of Time Award (2019). NSDI Test of Time Award (2023). AAAS Golden Goose Award (2021). Allen School ACM Teaching Award (2022). IEEE Fellow (2023).

Research. I strive to envision what the world might be like the next 5, 10, or 15 years, anticipate what risks and harms might arise (under various possible futures), and then proactively and ethically study those risks+harms and explore mitigations. I am particularly interested in (1) exploring new, previously unexplored technologies and research areas, (2) exploring existing research areas with novel, new approaches, (3) exploring issues of contemporary importance, (4) conducting work that is cross-disciplinary, (5) leveraging the best methodologies to explore the questions at hand (e.g., user studies, Internet crawlers, or experimental attack explorations), and (6) conducting work that is import to society and that recognizes that society and technology are deeply intertwined.

Example technology areas of study include:

Example themes that crosscut my research include:

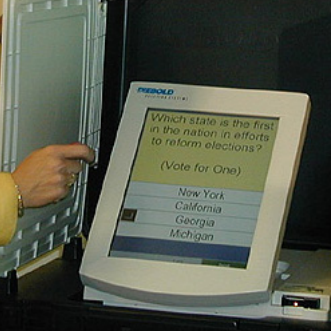

Electronic Voting Security: In 2003, my colleagues and I conducted the first academic security analysis of real electronic voting machine software. Our work played a pivotal role in the emerging national discussion of electronic voting security. I continued to work in electronic voting security until 2006, including co-chairing the USENIX/ACCURATE Electronic Voting Technology Workshop in 2008. I also testified before the U.S. House of Representatives, on the topic of electronic voting security.

Remote Physical Device Fingerprinting, Clock Skews, and Side Channels: In 2005, my colleagues and I discovered and studied mechanisms to remotely fingerprint physical devices by inferring information about their clock skews from their network packets. I have been told that the credit card industry uses my methods to help detect online credit card fraud. I continue to be interested in other forms of information leakage and side channels. For example, we studied the ability to infer what one is watching on TV by monitoring their powerline. We studied the ability to fingerprint automotive drivers by the ways in which they operated their vehicles. We also studied information leakage in the DNA sequencing pipeline.

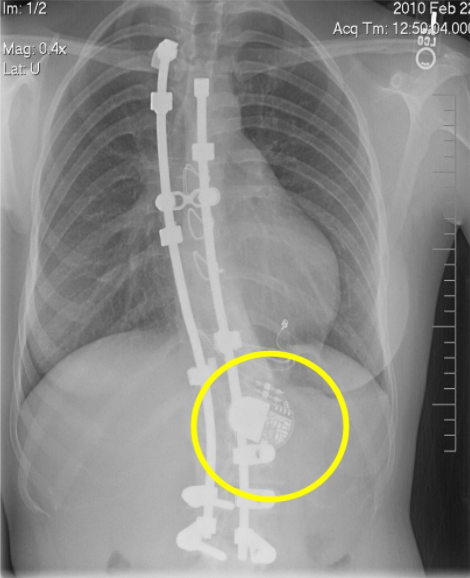

Wireless Medical Device Security: In 2008, my colleagues and I published the first academic security analysis of a real, wireless implantable medical device. This work helped initiate the field of medical device security and resulted in significant changes within industry and government. The executive producers of Homeland incorporated medical device security into their TV show after reading about our research. My subsequent work includes studies with patients and medical providers, and encompasses cardiac devices, insulin pumps and glucose monitors, telerobotic surgery, and brain-machine interface devices. For the latter, we coined the term neurosecurity. Our vision is outlined in a 2010 New England Journal of Medicine article. We co-founded the USENIX HealthSec conference in 2010. My ongoing work is focused on telerobotic surgery.

Automotive Computer Security: In 2010 and 2011, my colleagues and I published the first experimental computer security analyses of a modern automobile, including research results demonstrating the ability to remotely compromise a vehicle over cellular, Bluetooth, and other non-contact means. This work has been cited as the impetus for the creation of a $70M DARPA effort (HACMS) as well as significant changes within the automotive industry and government. This work also received the 2021 American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Golden Goose Award. This is our project page.

Augmented and Mixed Reality, Computer Security, and Privacy: In 2011, my colleagues and I initiated a research program focused on computer security and privacy risks with next-generation augmented and mixed reality technology. Our program began at a time before Google Glass (and many more recent technologies) were announced. Our research is broad and includes, for example, the design of systems, users studies, a collaboration with neuroscientists, and hosting an academic-industry workshop. This is our project page.

Computer Security and Smarthome Technologies: In 2012, my colleagues and I published a paper titled "Computer Security in the Modern Home." This paper articulated our vision for computer security and privacy for smarthome technologies, for the decades to come. Our 2012 article is based on work that we did prior to 2012. We continue to conduct research in this space. Example works include our discovery of security and privacy risks with wireless toy robots, our discovery that it is possible for devices monitoring a home’s powerline to infer information about what is being displayed on a TV, our discovery that it is possible for a compromised device controlling an electrical outlet to "pop" lightbulbs, and our study of security and privacy risks and practices when the owners of a residence are not the occupants (e.g., in the case of vacation rentals by owners).

Web Tracking, Privacy, and Ads: In 2012, my colleagues and I published one of the first measurement studies of the privacy risks with online web tracking. We continue to study the advertising ecosystem from a security and privacy lens. We used the Wayback Machine to retroactively study web tracking in the past. We explored the means by which the purchasers of ads can use the advertising ecosystem as a large-scale surveillance platform (see also minute 21:00 and onward of Last Week Tonight). We have also studied clickbait and deceptive ads on news and misinformation sites.

Tricking Computer Vision Algorithms with Physical Objects: In 2017, my colleagues and I wrote a paper studying the ability to trick computer vision algorithms with alterations to physical objects. Specifically, by strategic placement of stickers, we tricked a computer vision algorithm into interpreting a stop sign as a speed limit sign. This paper was published in 2018 and has been cited as part of the motivation for the creation of a $70M DARPA program (GARD). Our Stop Sign has been on display in at the Science Museum in London, in their exhibit on autonomous driving. This work inspired us to explore, from a legal perspective, whether tricking a robot is considered "hacking".

DNA + Biology + Computer Security: In 2017, my colleagues and I published a paper that studied, for the first time, the ability to compromise computer software with exploit code encoded in synthesized DNA. Figure 1 in our paper provides a photo of a test tube containing our synthesized DNA. In 2020, we published a study of privacy risks with genetic genealogy systems. We are calling this field "CyBio Security". I continue to research cybio security risks and defenses; this is our project page. Education (General). I care deeply about education, including helping students understand the importance of understanding and carefully considering the relationship between society and technology.

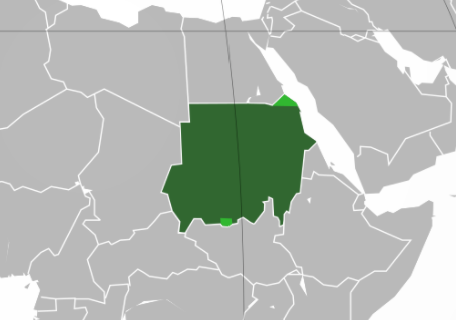

Specific Populations: I am and have been deeply interested in the computer security privacy needs and values of specific populations, including understudied populations. I have considered computer security for wireless children’s toys (2009), the relationships between parents and children (2010), medical device patients (2010), medical providers (2014), censorship in Thailand (2017), users of online dating systems (2017), refugees (2018), guests at vacation rentals that contain smart devices (2020), and activists during the Sudanese revolution (2021).

Contemporary Issues: I am deeply interested in studying issues of contemporary interest. In 2008, we published a largescale measurement study of whether and to what degree ISPs were modifying web pages inflight between the webserver and a user’s browser. In 2008, we experimentally found that it was possible to frame nonsensical devices (like IP printers) for illegal filesharing, resulting in those devices getting DMCA takedown orders. In 2009, we studied security and privacy risks with the (then) emerging Enhanced Drivers Licenses. In 2017, we published the results of our research aimed at detecting whether cities were deploying citywide cellphone surveillance devices (called IMSI catchers). In early 2020, we launched a longitudinal study of people’s privacy preferences with respect to COVID-19 contact tracing applications, and we also launched a study of people’s technology use (and security and privacy risks and perspectives) during the COVID-19 pandemic and increased work-from-home. In 2021, we published research focused on helping people protect themselves from unwanted face recognition. Games. I am passionate about exploring different methods of engaging people in educational content outside of the classroom. Games are one such method.

Early in my teaching career, I introduced "security reviews" and "current events" assignments into my undergraduate computer security courses. My goal was to help students learn to think broadly about technology and the relationship between society and technology. Wired provides a summary of my course’s use of "security reviews". I modeled the "current events" assignment off an assignment from my high school history course. For a more recent version of these assignments, see UW CSE 484 Winter 2022's homework 1 and homework 2; part 2 of this version of homework 1 is attributed to Justin Petelka, Megan Finn, Franziska Roesner, and Katie Shilton (see this paper).

In 2010, I co-authored Cryptography Engineering: Design Principles and Practical Applications. Quoting from the Wiley's (the publisher's) description: Cryptography is vital to keeping information safe, in an era when the formula to do so becomes more and more challenging. Written by a team of world-renowned cryptography experts, this essential guide is the definitive introduction to all major areas of cryptography: message security, key negotiation, and key management. You'll learn how to think like a cryptographer. You'll discover techniques for building cryptography into products from the start and you'll examine the many technical changes in the field.

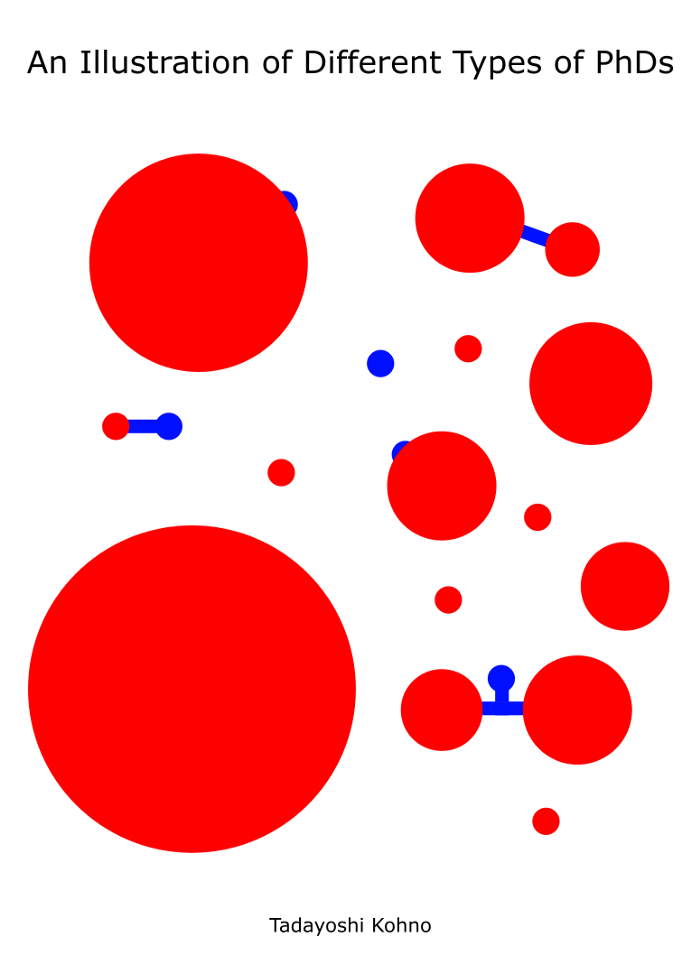

I am in the process of preparing a collection of Medium posts with advice for PhD students. I have one post about the classic PhD Bubble Diagram. I have another post on the unseen effort during the PhD process, "failures," and the Research Iceberg Analogy. Building on the Research Iceberg Analogy, I also have a post on the art of research paper writing. Fiction. I believe that fiction, like games, can help catalyze conversations and deep thinking about the relationship between people, society, and technology.

In 2012, my colleagues and I released a card game called Control-Alt-Hack, the goal of which was to help raise awareness about key computer security concepts, as well as the breadth of technologies that could be impacted by poor computer security design choices and the human impacts of security and privacy compromises. Toolkits. I believe that toolkits can help people (e.g., students in a classroom, researchers, industry practitioners) think critically and creatively about computer security risks and defensive opportunities.

In 2011, I published a short paper about my experience asking students to write science fiction short stories in a computer security course. By asking students to create and explore a fictional world, and to place technology in that fictional world, my goals was to help students think critically about the broader societal context for computing systems.

In 2020, I co-edited the UW Tech Policy Lab’s short story anthology, Telling Stories: On Culturally Responsive Artificial Intelligence.

In 2021, I published Our Reality, a novella written to contribute to discussions on society, racism, and technology; I also released a companion document that elaborators on the educational content in Our Reality.

In 2022, I joined the editorial board of the IEEE Security & Privacy Magazine, where I contribute a column titled "Off by One." The column strives to explore critical security and privacy topics in creative, non-traditional ways. Example columns include "Excerpts From the New Dictionary of Cybersecurity, 2036" and "Mx. President Has a Brain."

In addition to the examples above, please see the list of stories here.

In 2013, my colleagues and I released The Security Cards: A Security Threat Brainstorming Toolkit. The toolkit consists of 42 physical cards designed to assist in computer security-related brainstorming and education. The are four card suits: Human Impact, Adversary's Motivations, Adversary's Resources, and Adversary's Methods.